RhoA-ROCK Pathway is Important for T-Cell Migration in a Mouse Stroke Model

Alba Manresa-Arraut, Morten Müller Aagaard, Cord Brakebusch, Henrik Hasseldam and Flemming Fryd Johansen

Alba Manresa-Arraut1*, Morten Müller Aagaard1, Cord Brakebusch2, Henrik Hasseldam1 and Flemming Fryd Johansen1

1Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, Neuroinflammation Unit, Biotech Research and Innovation Centre (BRIC), University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

2Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, Cytoskeletal Organization Group, Biotech Research and Innovation Centre (BRIC), University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

- *Corresponding Author:

- Alba Manresa-Arraut

Faculty of Healthand Medical Sciences

Biotech Research and Innovation Center

University of Copnehagen

Ole Maaløes Vej, 5 2200 KBH N, Denmark

Tel: (+45)81939353

E-mail: a.manresa.arraut@gmail.com

Received Date: November 23, 2017; Accepted Date: December 10, 2017; Published Date: December 14, 2017

Citation: Manresa-Arraut A, Aagaard MM, Brakebusch C, Hasseldam H, Johansen FF (2017). RhoA-ROCK Pathway is Important for T-Cell Migration in a Mouse Stroke Model. J Transl Neurosci 2:3.

Abstract

The small Rho GTPases tightly regulate the cell’s contractility, motility and morphology. Among these, the small GTPase RhoA is the main regulator of T-cell migration. Using T-cell-specific RhoA knock-out mice (RhoAfl/flLckCre+) we hereby show the importance of RhoA expression in the T- cell’s transendothelial migration capacity and in the T-cells’ brain infiltration in an infarct mouse model. We observed that T-cells lacking RhoA expression (RhoA-/- T-cells) present a ~20% reduction in their capacity of transmigrating across an endothelium compared to wild type RhoA+/+ T-cells. We also investigated how the inhibition of RhoA signaling affected the post-stroke T-cell response in mice, 21 days after pMCAO and found that lack of RhoA expression markedly reduces T-cells migration into the infarcted brain, evidenced by the presence of significantly less CD3+ cells within the infarct area of RhoAfl/flLckCre+ mice compared to control mice. T-cell infiltration into the infarcted brain was not affected when mice were treated with atorvastatin, an inhibitor upstream of RhoA, and fasudil, an inhibitor of the RhoA downstream kinase ROCK. This highlights for the first time RhoA as a key regulator in T-cell transmigration into infarcted brain tissue. Taken together, these results suggest that the activity of the small GTPase RhoA is crucial for T-cells ability to migrate across an endothelial cell layer and into the infarcted brain. It also underlines the therapeutic potential of the RhoA-ROCK pathway in diseases in which cell migration is important for their pathophysiology, such as immunological diseases or cancer.

Keywords

RhoA; Transmigration; Ischemic stroke

Introduction

Small Rho GTPases are known to play multiple roles in cytoskeletal rearrangement and cell migration, and are therefore of therapeutic interest in a range of diseases such as cancer and autoimmunity [1]. The Rho GTPase family consists of 20 members that act like molecular switches, active when bound to GTP and inactive when bound to GDP, and are controlled by guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEF’s), GTPase activating proteins (GAPs) and guanine dissociation inhibitors (GDIs). One of the main Rho GTPase subfamilies comprises the Rho proteins RhoA, RhoB and RhoC, which are intimately involved in cell migration. Through the Rho- associated protein kinase (ROCK), they control a range of downstream kinases such as myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), which activates myosin, cofilin and is involved in actin rearrangement and stabilization, and the Na+/H+-exchanger (NHE1), which is required for focal adhesion formation [2].

RhoA is one of the main Rho-GTPases involved in T-cell migration [3]. It regulates the formation of stress fibers, actomyosin contractility, and detachment of the uropod at the trailing edge [3,4]. Knock-down of RhoA resulted in decreased migration of T-cells across a monolayer of HUVECs [3], depletion of GEF-H1 (a GEF that controls RhoA activity) and attenuated cell contractility through decreased phosphorylation of MLC [5]. These in vitro studies point out the crucial role of RhoA in T-cell migration.

Statins are known to have several effects on inflammatory reactions such as suppression of Th1 and Th17 responses, decreased MHC class II expression and inhibition of LFA-1 binding. These effects are partially mediated through induction of the anti-inflammatory transcription factors peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) [6], but also by preventing isoprenylation of Rho GTPases and thereby inhibiting their downstream signaling [7].

The ROCK inhibitor fasudil has a long history of safe clinical application with relatively mild side effects, and is therefore a promising therapeutic resource for inflammatory diseases [8-10]. A variety of models have shown anti- inflammatory effects of this compound. Satoh and co-workers showed that fasudil treatment reduced the levels of infiltrating neutrophil granulocytes after brain ischemia while at the same time reducing brain infarction [11]. Fasudil has also been shown to inhibit neutrophil tissue infiltration in mouse models of acute lung injury and systemic inflammation [12,13]. In experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, brain infiltration of immune cells was reduced upon fasudil treatment [14,15].

The role of the immune response following cerebral infarction is highly complex and several reports point towards opposite effects of lymphocytes depending on the micro milieu and temporal evolution [16,17]. Classically, T-cells have been considered as harmful in the post-stroke disease paradigm but more recently, the T-cell phenotype seems to determine whether it is deleterious or, in fact, neuroprotective [17-20]. The exact mechanisms that govern these effects are not fully understood, primarily because of a highly complex interplay between the numerous mediators.

In this study we investigated whether T-cells that lack RhoA are functionally impaired with regards to their transmigratory abilities in a trans endothelial migration assay and in a brain infarction mouse model. To broaden our analysis and understanding of the RhoA-ROCK pathway, we included atorvastatin and fasudil treatment in the study. We report for the first time that RhoA plays a crucial role in T-cell transmigration into infarcted brain tissue.

Materials and Methods

Experimental animals

Mice with a T-cell-restricted deletion of the RhoA gene (RhoAfl/ flLckCre+) were generated using the Cre-loxP system as described previously and kept as a 129Sv/C57Bl/6 outbred strain [21,22]. RhoA wild type (RhoAfl/flLckCre-), RhoA heterozygous (RhoAfl/+LckCre+) and RhoA knock-out (RhoAfl/flLckCre+) mice were bred and housed in the AAALAC certified animal facility at the Biotech Research and Innovation Center, University of Copenhagen. Mice were housed 2 to 6 animals per IVC cage with free access to food and water on a 12 h light/dark cycle. All procedures were approved and performed in accordance with the Danish Animal Experimentation Committee (#2012-DY-2934- 00001) and the European Council Directive #86/609 for the Care of Laboratory Animals.

Induction of permanent cerebral artery occlusion (pMCAO)

Mice were anesthetized with 2-3% isoflurane (Forene, Abbot Scandinavia, Stockholm, Sweden) delivered in pure oxygen. Focal cerebral ischemia was induced by permanent occlusion of the distal part of the right middle cerebral artery, as previously described [23]. In connection to the subsequent suture, mice received a subcutaneous administration of lidocaine (10 mg/ml, Glostrup Apotek, Glostrup, Denmark).

Experimental groups

A total of 54 mice between 9 and 18 weeks of age were included in the study. Of those, 17 mice were excluded due to death during surgery, unsuccessful surgery or brain tissue damage during tissue processing. Seven days after surgery, the mice were randomly divided into groups and treated daily for 14 days. Group 1: Control animals, intraperitoneal (ip.) administration of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) + 10% EtOH, (RhoAfl/flLckCre- n=7, RhoAfl/flLckCre+ n=5); group 2: subcutaneous (sc) administration of Atorvastatin in a PBS + 10% EtOH based solution of 2 mg/ ml (200 μg/100 μl injection, Pfizer®, New York, USA) (RhoAfl/ flLckCre- n=10, RhoAfl/flLckCre+ n=3); group 3: ip administration of fasudil in ddH2O-based solution of 3 mg/ml (10 mg/kg, HA-1077 dihydrochloride, Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany), (RhoAfl/ flLckCre- n=7, RhoAfl/flLckCre+ n=5).

Brain tissue and T-cell preparation

Twenty-one days after pMCAO, mice were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane (Forene, Abbot Scandinavia) delivered in pure oxygen. Mice were perfused transcardially with PBS until blood was cleared from the circulation, followed by 100 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde (VWR International, Leuven, Belgium). Brains were collected and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for at least 24 h before they were embedded in paraffin. Using a microtome, 3 μm coronal sections of tissue were collected in 12 levels with 400 μm between each level. Sections were mounted on superfrost plus slides (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, USA) and kept at 40°C overnight to dry, followed by histological or immunohistochemical staining. One section from each of the 12 levels was randomly chosen for hematoxylin and eosin staining.

For the in vitro T-cell transendothelial migration study, splenic CD3+ T-cells were isolated from RhoAfl/flLckCre- or RhoAfl/flLckCre+ mice using a MACS Pan T-cell isolation kit II mouse (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). T-cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Thermo Fischer Scientific) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and IL-2 (5 ng/ml, BioLegend) at a concentration of 106 cells/ml in 6-well plates (Corning Costar, Tewksbury, USA) and stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 (3 μg/ml, BioLegend, San Diego, USA), anti-CD28 (3 μg/ml, BioLegend) for 24 h.

Immunohistochemistry

Four brain sections within the infarct area were chosen for CD3 staining. Briefly, sections were rehydrated through xylene and decreasing series of ethanol (99%, 96% and 70%) and rinsed in PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBS-T) (Gibco, Thermo Fischer Scientific). Antigen retrieval was performed by steaming for 20 min in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH=6, Sigma-Aldrich) followed by 20 min at room temperature. Sections were rinsed in PBS-T and blocked with 5% goat serum (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) for 30 min at room temperature. The sections were incubated over night at 4°C with monoclonal rabbit anti-mouse CD3 antibody (1:100, Abcam, Cambridge, UK). The sections were rinsed in PBS-T and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated polyclonal goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:400, Abcam). Then sections were rinsed with PBS-T and incubated with diaminobenzidine (DAB) for 7 min. Sections were rinsed again in PBS-T before counterstained with hematoxylin for 20 seconds and dehydrated through increasing concentrations of ethanol (70%, 96%, 99%) and xylene. Sections were mounted with DPX mounting media (Cellpath, Newtown, UK).

Estimation of infarct volume

All micrographs from the hematoxylin and eosin stained sections were obtained by scanning whole sections using a NanoZoomer- 2.0HT (Hamamatsu, Japan) at 40X magnification. Infarct areas of each brain slice were estimated manually using of the “Freehand region” function in the NDP.view 2 software (Viewing software, Hamamatzu, www.hamamatzu.com). The area was measured from all the brain sections in which the infarct was present. The infarcted region was identified by its characteristic morphology that differs from the surrounding healthy tissue and from the same brain region of the healthy contralateral hemisphere. The trapezoid formula was used to determine the infarct volume, by calculating the mean of the infarct area of two neighboring sections and multiplying by the distance between the two (400 μm).

T-cell quantification

All microscopy images from stained sections were obtained by scanning whole sections using a NanoZoomer-2.0HT (Hamamatsu, Hamamatsu City, Japan) at 40X magnification. All CD3+ cells within the infarct area were manually quantified and plotted as total CD3+ cells per mm2 of infarct, measured using the “Freehand region” function in the NDP.view 2 software (Viewing software, Hamamatzu). The anatomical regions were identified using the haematoxylin staining. Four random sections containing infarcted tissue were quantified by two blinded observers using the QuPath open source software for digital pathology image analysis (https://qupath.github.io/) [24].

Active and total RhoA and ROCK determination

The mouse lymphoma cell line EL-4 was used to analyze the effects of atorvastatin and fasudil on the levels of active and total RhoA as well as its downstream kinase ROCK. A total of 2.5 x 106 cells in 2 ml DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) +10% fetal calf serum (Sigma-Aldrich) were treated with atorvastatin calcium salt trihydrate (1, 5 or 20 μM, Sigma) and fasudil (3, 15 or 75 μg/ ml, Sigma) for 24 h. After washing, the cells were lysed in 0.5M Tris-HCl (pH=7.5) + 10 mM MgCl2+ 1% Igepal + protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete mini, Roche, Mannheim, Germany), followed by centrifugation (12000 x g, 10 min) and protein quantification (Precision red advanced protein assay, Cytoskeleton, Inc Denver, USA). Quantification of active and total RhoA (Cytoskeleton, Inc,) as well as ROCK (MyBioSource, San Diego, USA) was performed using commercially available ELISA assays, according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Toxicity of the two compounds was tested with the LDH release assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

T-cell transendothelial migration study

The T-cell transmigration assay was performed in polycarbonate Transwell™ filter inserts of 8 μm pore size (Corning Costar) covered with a confluent monolayer of mouse brain endothelial bEnd.3 cells. bEnd.3 cells (passage number>30) from confluent 10 cm2 dishes (Corning Costar) were trypsinized and plated onto the Transwell™ filter inserts at a seeding density between 5 x 104 and 105 cells/cm2 in 100 μl of DMEM medium (Thermo Fischer Scientific) supplemented with 10% FCS, penicillin G (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Culture medium was changed every 48-72 h. Splenocytes were CD3+ enriched by magnetic sorting as described above and activated with plate- bound anti- CD3 (3 μg/ml, BioLegend) and anti-CD28 (3 μg/ml, BioLegend) for 24 hrs. When bEnd.3 cells were confluent after 5 days of culture, the culture medium was removed and 100 μl of activated T-cells (5 x 104 T-cells/well) in serum-free 1640 RPMI medium were placed in the upper chamber, and 600 μl of fresh serum-free 1640 RPMI medium was added in the bottom chamber of the Transwell™. The plates were then incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 in the IncuCyte ZOOM® (Essen BioScience, Ann Arbor, USA) for live-cell time lapse imaging of the transmigrated cells. Nine images per well from three technical replicates were taken every 30 min for 4 h using a 20x objective lens and then analyzed using the IncuCyte™ Basic Software. In phase contrast, cell segmentation was achieved by applying a mask in order to exclude cells from background. An area filter was applied to exclude objects below 10 μm2. After 4 h the transmigrated T-cells present in the bottom chamber were recovered and quantified using the Accuri™ C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, USA). Data analysis was done using the FlowJo V10 software (Tree Star).

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean. The analysis of the atorvastatin and fasudil effect on RhoA and ROCK activity was done using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test. The differences between groups in the T-cell transendothelial migration assay were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was used to analyze differences in the amount of CD3+ T-cells within the infarcted area between the groups. The analysis of the differences in infarct volume between groups was done using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. All analyses were performed using Prism 7 (GraphPad Prism software) and considered significant at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

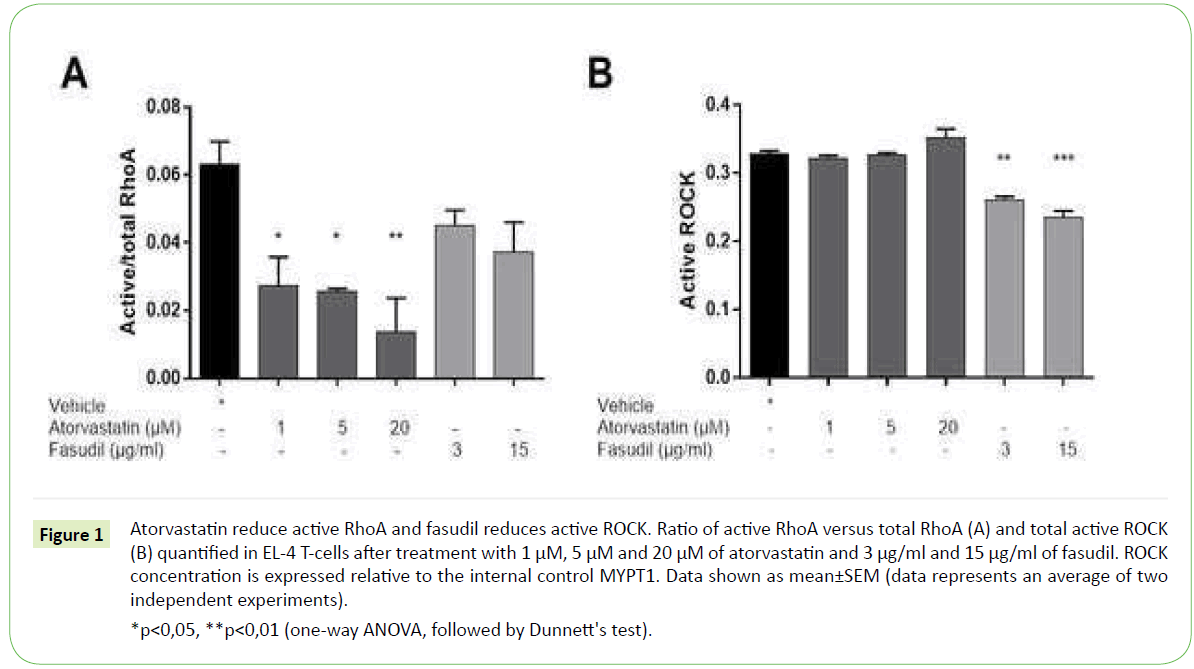

Atorvastatin and fasudil reduce RhoA and ROCK activity in T-cells

To determine the optimal concentrations of the two compounds, titration assays were performed followed by measurements of active RhoA, total RhoA and active ROCK in the mouse T-cell line EL- 4 after 24 h of treatment with atorvastatin and fasudil in various concentrations. Atorvastatin inactivates RhoA by inhibiting its isoprenylation; therefore, we expect a reduction of active RhoA upon treatment. Fasudil is a RhoA downstream ROCK kinase inhibitor, and as such it might not affect the activity of RhoA.

Our results show that atorvastatin at the concentrations of 1, 5 and 20 μM significantly inhibits active RhoA in EL-4 cells, with a decrease of ~55%, ~60%, and ~80%, respectively. Fasudil treatment of EL-4 cells with 3 μg/ml and 15 μg/ml resulted in a ~30% and ~40% reduction of active RhoA, which could signify a negative feedback response Figure 1A. Neither atorvastatin nor fasudil treatment affected the total RhoA levels in EL-4 cells (data not shown).

*p<0,05, **p<0,01 (one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett's test).

Figure 1: Atorvastatin reduce active RhoA and fasudil reduces active ROCK. Ratio of active RhoA versus total RhoA (A) and total active ROCK (B) quantified in EL-4 T-cells after treatment with 1 μM, 5 μM and 20 μM of atorvastatin and 3 μg/ml and 15 μg/ml of fasudil. ROCK concentration is expressed relative to the internal control MYPT1. Data shown as mean±SEM (data represents an average of two independent experiments).

We observed no changes in ROCK activity after treatment with 1, 5 and 20 μM of atorvastatin Figure 1B. Given that atorvastatin inhibition is upstream of ROCK [7,25], it might be that other mediators along the signaling cascade activate ROCK in vitro despite the inhibitory effect of atorvastatin. On the contrary, upon treatment with 3 μg/ml and 15 μg/ml fasudil we observed a reduction of ROCK activity by 20% and 30% respectively when compared to vehicle-treated cells Figure 1B. This effect was expected, as fasudil is a relatively selective ROCK inhibitor [26].

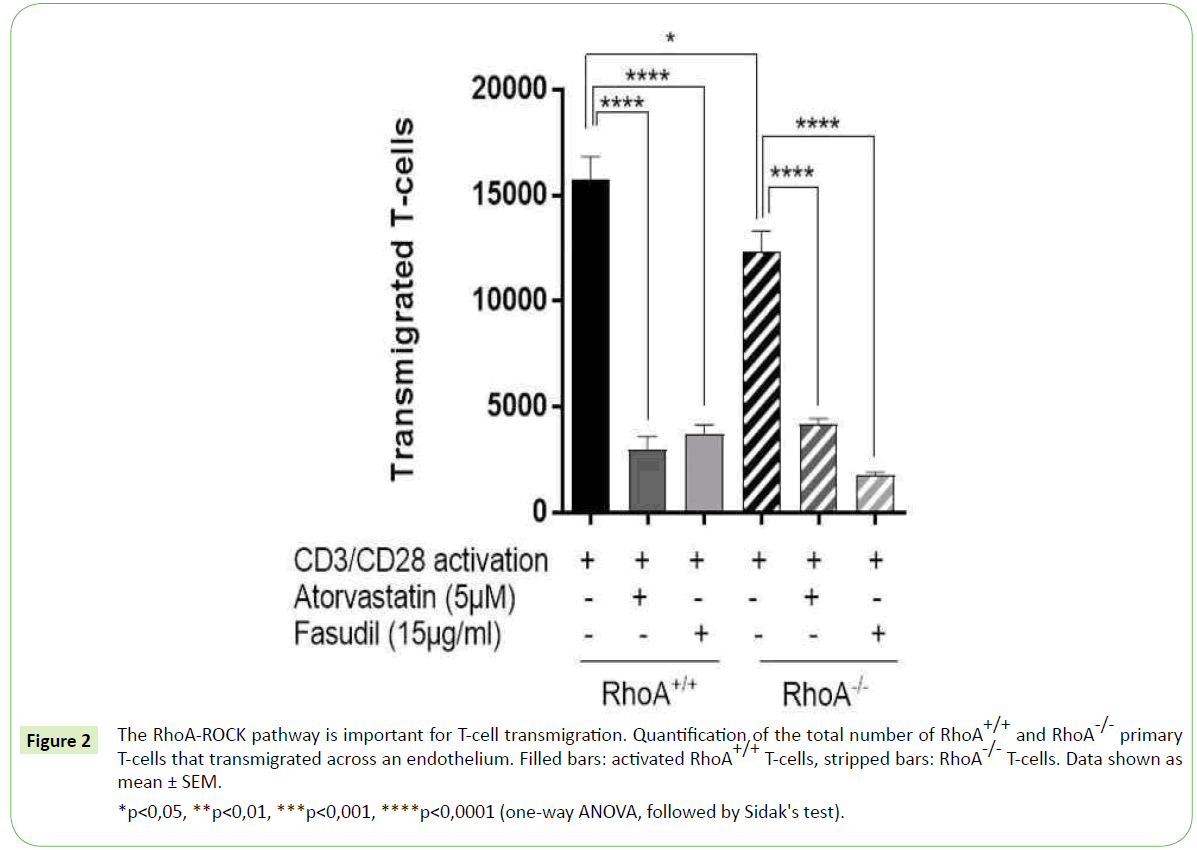

RhoA-ROCK signaling is important for T-cell transmigration

Given that RhoA-ROCK signaling pathway is involved in T-cell migration [3,4], we investigated whether the deletion of RhoA in T-cells would affect their transmigration capacity. To that end we monitored the ability of T-cells with and without RhoA expression (RhoA+/+ and RhoA-/- T-cells, respectively) to migrate across a confluent layer of endothelial cells for 4 hours. We observed that the lack of RhoA expression results in significantly fewer T-cells (~20% reduction compared to RhoA+/+) transmigrating across the endothelial barrier Figure 2. However, a significant amount of RhoA-/- T-cells could migrate across the endothelium, which might point towards a compensatory effect of the RhoA homologs RhoB and RhoC when RhoA signaling is lacking.

*p<0,05, **p<0,01, ***p<0,001, ****p<0,0001 (one-way ANOVA, followed by Sidak's test).

Figure 2: The RhoA-ROCK pathway is important for T-cell transmigration. Quantification of the total number of RhoA+/+ and RhoA-/- primary T-cells that transmigrated across an endothelium. Filled bars: activated RhoA+/+ T-cells, stripped bars: RhoA-/- T-cells. Data shown as mean ± SEM.

To further characterize the role of RhoA-ROCK signaling in T-cell transmigration, we treated RhoA+/+ and RhoA-/- T-cells with 5 μM atorvastatin for 24 hours or with 15 μg/ml fasudil for 48 hours prior migration. T-cell transmigration was dramatically reduced upon treatment with both compounds, respectively with an 80% and 75% reduction in RhoA+/+ T-cells and 65% and 85% reduction in RhoA+/+ T-cells when compared to their non-treated control T-cells Figure 2. The inhibitory effect of atorvastatin and fasudil was significant in all T-cells independently of their RhoA expression, which is probably because of the inhibition of the RhoA-ROCK pathway in a broader scale compared to when only the RhoA expression is lacking.

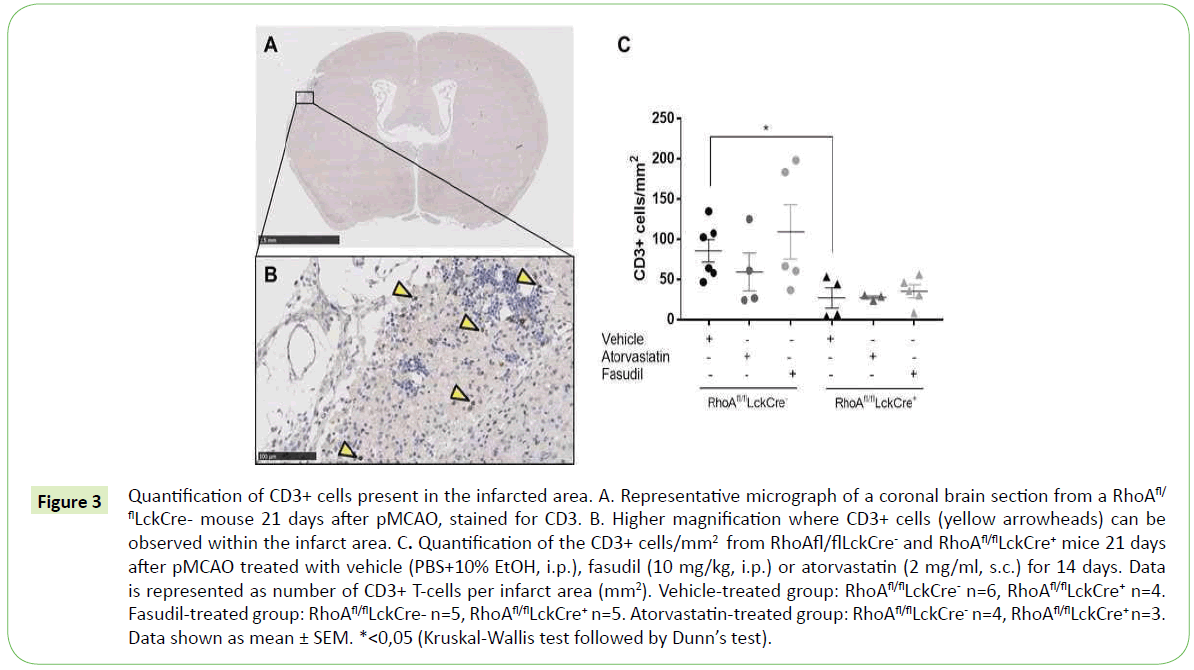

RhoA is important during T-cell infiltration into the infarcted brain

As observed in our in vitro transmigration assay, inhibition of the RhoA-ROCK signaling in T-cells significantly reduces their trans migratory capacity. It is known that T-cells migrate to the brain in high numbers several weeks after an ischemic insult [16], so it was therefore interesting to investigate whether lack of RhoA in T-cells affects T-cell migration also in vivo. We induced an ischemic stroke to RhoAfl/flLckCre- and RhoAfl/flLckCre+ mice using the model permanent occlusion of the middle cerebral artery (pMCAO) and analyzed the number of infiltrated T-cells in the infarct area 21 days after ischemic insult (Figure 3A and 3B).

Figure 3: Quantification of CD3+ cells present in the infarcted area. A. Representative micrograph of a coronal brain section from a RhoAfl/ flLckCre- mouse 21 days after pMCAO, stained for CD3. B. Higher magnification where CD3+ cells (yellow arrowheads) can be observed within the infarct area. C. Quantification of the CD3+ cells/mm2 from RhoAfl/flLckCre- and RhoAfl/flLckCre+ mice 21 days after pMCAO treated with vehicle (PBS+10% EtOH, i.p.), fasudil (10 mg/kg, i.p.) or atorvastatin (2 mg/ml, s.c.) for 14 days. Data is represented as number of CD3+ T-cells per infarct area (mm2). Vehicle-treated group: RhoAfl/flLckCre- n=6, RhoAfl/flLckCre+ n=4. Fasudil-treated group: RhoAfl/flLckCre- n=5, RhoAfl/flLckCre+ n=5. Atorvastatin-treated group: RhoAfl/flLckCre- n=4, RhoAfl/flLckCre+ n=3. Data shown as mean ± SEM. *<0,05 (Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test).

As expected, we observed a significant number of T-cells in the infarct area in RhoAfl/flLckCre- mice 21 days after pMCAO (Figure 3C) and significantly reduced number of T-cells in the infarcted site of the brains from RhoAfl/flLckCre+ mice. This contrast indicates that RhoA-ROCK signaling pathway plays an important role in T-cell migration to the brain parenchyma (Figure 3C).

To examine more in detail the role of the RhoA-ROCK signaling pathway in T-cell brain infiltration we treated RhoAfl/flLckCre- and RhoAfl/flLckCre+ mice with atorvastatin (2 mg/ml, s.c.), fasudil (10 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle for 14 days starting 7 days after pMCAO. Surprisingly, treated mice presented similar numbers of infiltrated T-cells in the infarct site compared to untreated RhoAfl/flLckCre- and RhoAfl/flLckCre+ mice. These results suggest that RhoA is a main regulator of T- cell brain infiltration, as inhibition upstream or downstream RhoA seems not to contribute to the inhibition of T-cell migration.

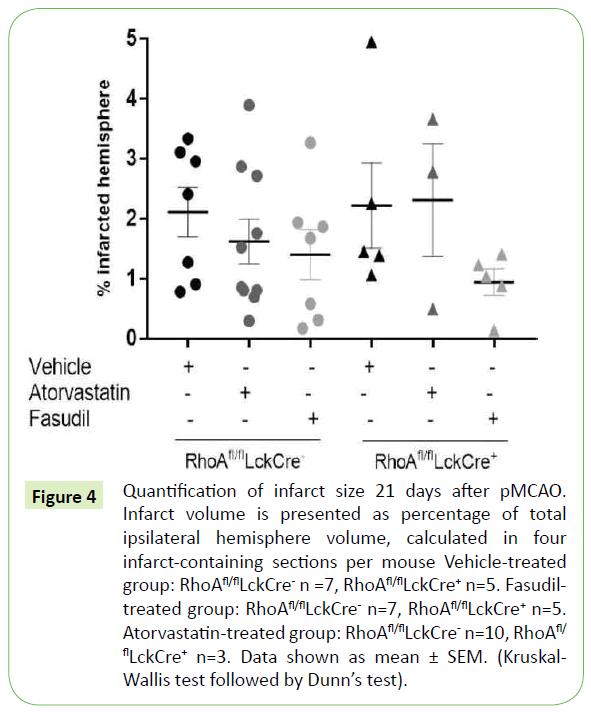

Lack of Rho-ROCK signaling does not affect the infarct size

Although T-cells have been classically associated with tissue damage after stroke, recent studies have described both detrimental and neuroprotective roles of T-cells depending on their phenotype [17-20]. In this study we investigated whether the presence of T-cells in the infarct area had an impact on the ischemic lesion size.

When measuring the ischemic lesion volume in RhoAfl/flLckCre- and RhoAfl/flLckCre+ mice 21 days after pMCAO we observed that, despite the fact that RhoAfl/flLckCre+ mice had significantly less T- cells within the infarct area compared to RhoAfl/flLckCre- mice (Figure 3), the infarct lesion size was similar in both groups (Figure 4). The infarct size was also unaffected in RhoAfl/flLckCre- and RhoAfl/flLckCre+ mice treated with atorvastatin (Figure 4). In the case mice treated with fasudil we observed a tendency to a reduced infarct size after treatment both in RhoAfl/flLckCre- mice (~25% reduction) and RhoAfl/flLckCre+ mice (~60% reduction) compared to the untreated mice, although the differences were not significant. The fact that the treatment was not given shortly after MCAO but 7 days after could be one of the reasons why the treatment did not impact the lesion size.

Figure 4: Quantification of infarct size 21 days after pMCAO. Infarct volume is presented as percentage of total ipsilateral hemisphere volume, calculated in four infarct-containing sections per mouse Vehicle-treated group: RhoAfl/flLckCre- n =7, RhoAfl/flLckCre+ n=5. Fasudil treated group: RhoAfl/flLckCre- n=7, RhoAfl/flLckCre+ n=5. Atorvastatin-treated group: RhoAfl/flLckCre- n=10, RhoAfl/ flLckCre+ n=3. Data shown as mean ± SEM. (Kruskal- Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test).

Discussion

In this study we demonstrated that the small GTPase RhoA plays a fundamental role in T-cell’s ability to transmigrate across an endothelium. We showed the importance of the RhoA-ROCK pathway in this process and we studied its role in T-cell transmigration following brain infarction.

Small Rho GTPases tightly regulate the cell’s contractility, motility and morphology. Through the downstream effector kinase ROCK, Rho GTPases control a range of downstream effectors that regulate actin cytoskeleton formation and stabilization as well as formation of focal adhesions [2].

Previous research has shown that among different Rho GTPases, RhoA is the main director of T- cell migration [3]. The activity of RhoA has been shown to be important in different steps of T-cell transmigration in several cell culture experiments [3,4] as well as in an in vivo model of thymocyte development that used LckC3 transgenic thymocytes with a Rho loss-of-function [27]. The role of RhoA in cell migration has also been shown important in cancer metastasis by using ex vivo imaging to study cell migration in a tumor microenvironment [28]. In the present study, using T-cell- specific RhoA knock-out mice (RhoAfl/flLckCre+ mice) we showed that RhoA expression in the T-cells is important for their transendothelial migration capacity, evidenced by the significantly lower transmigration of RhoA-/- T-cells across an endothelium compared to RhoA+/+ T-cells.

Cell migration is a highly complex process that involves the cell surroundings, several cellular compartments and various signaling pathways, as it has been extensively reviewed [29]. The RhoA-ROCK pathway has been previously investigated in this respect, and the inhibitors of this pathway, statins and fasudil, have been shown to inhibit T-cell migration in various disease models [1,30-32].

Statins are 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors and they are widely used for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Beyond cholesterol reduction, statins have neuroprotective properties which are independent of the lipid-lowering ability such as the inhibition of isoprenoid intermediates [33,34]. Isoprenylation is an important post-transcriptional modification of small Rho GTPases like RhoA and is critical for their proper intracellular localization and function [25]. It is suggested that it is through this pathway that statins exert anti-inflammatory effects [7].

Fasudil targets ROCK, a RhoA downstream effector kinase. ROCK presents two isoforms, and various studies using ROCK knock-out mouse models and ROCK inhibitors have pointed out their differential biological functions and regulation [35-38]. For example, a study using ROCK1 and ROCK2 knock-outs in mouse embryonic fibroblasts, ROCK1 was suggested to be responsible for destabilizing the actin cytoskeleton while ROCK2 accounted for the actin cytoskeleton stabilization [36]. Despite their functional differences, the two isoforms share ~65% of their sequence and ~92% of their ATP binding pocket [39], which is the binding site of fasudil [10]. Fasudil is therefore a non-isoform specific ROCK inhibitor and it has been shown to be a potent inhibitor and relatively more selective to ROCK than to other serine/threonine kinases [26].

Prior to our functional experiments using fasudil and atorvastatin, we did a titration of both compounds and studied their effect on RhoA and ROCK activity in the EL-4 cell line. Our results show that atorvastatin treatment significantly reduced the levels of active RhoA. Surprisingly, the activity of the RhoA downstream effector ROCK was not affected by atorvastatin treatment.

Several Rho-independent ROCK activation pathways have been described that could explain the lack of effect upon atorvastatin treatment. For example, ROCK activation by lipid stimulation has been reported, especially by arachidonic acid [40,41], and ROCK-2 can be activated by PI-3 kinase [38]. The low atorvastatin concentration used could also explain our results, and it is possible that higher concentrations of atorvastatin could result in a reduction of active ROCK. However, the poor solubility of atorvastatin in aqueous buffers resulted in DMSO-mediated cytotoxicity at concentrations above 20 μM. Treatment with the ROCK-selective inhibitor fasudil resulted in a slight reduction of active RhoA, and caused a significant reduction of the levels of active ROCK. The slight decrease of active RhoA after fasudil treatment, although non-significant, is probably mediated by a negative feedback loop via TIAM1- Rac1 stimulation as reported previously [42].

Using our transendothelial migration model we showed that when inhibiting the RhoA-ROCK pathway, either by knocking out RhoA expression or by pharmacologically inhibiting the pathway upstream of RhoA with atorvastatin or downstream of RhoA with fasudil, T-cell transmigration is markedly reduced. These results underline the therapeutic potential that the RhoA-ROCK pathway may have in diseases in which cell migration is important for their pathophysiology, such as immune-mediated diseases or cancer.

Previous studies as well as our results discussed above showed that the interference with the RhoA-ROCK signaling pathway can impair T-cells’ function and migration [1,11]. RhoA tightly regulates the expression of integrins, and it has been shown that RhoA is sufficient for the β1 and β2 integrin-mediated thymocyte adhesion [27].

Furthermore, it has been shown that the endothelial expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and 2 (ICAM-1 and ICAM-2, respectively), which bind to β2 integrin in T-cells, are essential for the T-cell transendothelial migration across the bloodbrain barrier [43]. In the present study we investigated how the inhibition of RhoA signaling affected the post-stroke T-cell response in mice 21 days after pMCAO. Lack of RhoA expression significantly reduced T-cell migration into the infarcted brain, as shown by the presence of significantly less CD3+ cells within the infarct area in RhoAfl/flLckCre+ mice compared to RhoAfl/flLckCremice. This confirms in vivo the importance of RhoA expression in T-cell migration that we had observed in our in vitro T-cell transendothelial migration study. Neither the treatment with fasudil nor atorvastatin resulted in a decrease of the CD3+ cells present in the infarct site. This was surprising given the strong inhibition of T-cell transmigration that we observed in our in vitro trans endothelial study upon treatment of T-cells with fasudil or atorvastatin. This could indicate that the atorvastatin and fasudil inhibitory effect on T-cells is not as strong when it is systemically administered in mice compared to when isolated T-cells are treated in vitro. Also, it could suggest that T-cells lacking RhoA have other biological functions impaired in addition to migration. Indeed, Rho GTPases are known to play a role in T-cell development, viability and activation [44,45].

When investigating the role of RhoA-ROCK signaling in the development of an ischemic infarct lesion, we found that the lesion size was not affected by the lack of RhoA in T-cells or by the treatment with the inhibitors of RhoA-ROCK signaling atorvastatin and fasudil. We chose the Atorvastatin dose based on previous studies using the murine stroke model, in which statin treatment resulted in reduced infarct lesion [46], induced brain plasticity and functional recovery [47]. Previous studies reported that the dose of fasudil used in our ischemic stroke model is optimal for obtaining the greatest efficacy and reduced infarct lesion [8,48]. Despite these evidences, we did not observe infarct reduction after atorvastatin or fasudil treatment. This could be due to the chosen time of treatment, as in the mentioned studies atorvastatin and fasudil are given 24 h [47] and up to 48 h [8] respectively, while in our study treatment started 7 days after MCAO. The later treatment starting time point in this study aimed at targeting primarily T- cells and macrophages, which are known to infiltrate into the brain at later stages, around day 7 after pMCAO [16].

The fact that we did not observe infarct size reduction upon atorvastatin and fasudil treatment also evidences the complexity of the RhoA-ROCK pathway, which has been previously described [3,49,50]. Nevertheless, complete absence of RhoA signaling significantly impeded T-cell migration into the infarcted brain, which suggests RhoA as a key regulator in this respect.

T-cells affect the infarct development in a dual way depending on the micro milieu and temporal evolution [16,17]. T-cells have been demonstrated to contribute both to tissue damage as well as to tissue repair following cerebral infarction [17- 20,51,52]. In our model, lack of T-cells in the infarct of RhoAfl/ flLckCre+ mice did not result in a change in infarct size in those mice, and treatment with fasudil after pMCAO resulted in a slight reduction in infarct size both in the RhoAfl/flLckCre+ and RhoAfl/ flLckCre- mice. This reduction is most likely not a T-cell mediated effect, given that these mice presented similar amounts of CD3+ T-cells within the infarct compared to the vehicle-treated mice. The neuroprotective effects of ROCK inhibition are thought to be predominantly linked to the increased endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression, which leads to production of the vasodilator nitric oxide (NO) thus increasing the blood flow and benefiting ischemic areas [26]. In a model of spinal cord injury, fasudil showed neuroprotective effects by regulating microglial activation and inhibiting neuronal apoptosis [53]. In the same line, fasudil treatment resulted in a lowering of neutrophil accumulation, reduction of the infarct lesion and improvement of neurological functions in rat and mouse models of brain ischemia [11,48,54].

Taken together, these data suggest that the activity of the small GTPase RhoA is crucial for the T- cells’ ability to migrate across an endothelial cell layer and into the infarcted brain. Fasudil-based treatments have a long history of safe clinical application with relatively mild side effects [10], and it has been successfully used in small trials in both CNS [55] and cardiovascular [56] diseases. Thus, we suggest the RhoA-ROCK pathway as an emerging promising therapeutic resource for inflammatory diseases.

References

- Biro M, Munoz MA, Weninger W (2014) Targeting Rho-GTPases in immune cell migration and inflammation. Br J Pharmacol 171: 5491-5506.

- Riento K, Ridley AJ (2003) Rocks: multifunctional kinases in cell behaviour. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4: 446-456.

- Heasman SJ, Carlin LM, Cox S, Ng T, Ridley AJ (2010) Coordinated RhoA signaling at the leading edge and uropod is required for T cell trans endothelial migration. J Cell Biol 190: 553-563.

- Heasman SJ, Ridley AJ (2010) Multiple roles for RhoA during T cell transendothelial migration. Small GTPases 1: 174-179.

- Pollock JK, Verma NK, O'Boyle NM, Carr M, Meegan MJ, et al. (2014) Combretastatin (CA)-4 and its novel analogue CA-432 impair T-cell migration through the Rho/ROCK signalling pathway. Biochem pharmacol 92: 544-557.

- Khattri S, Zandman-Goddard G (2013) Statins and autoimmunity. Immunol Res 56: 348-357.

- Bu DX, Griffin G, Lichtman AH (2011) Mechanisms for the anti-inflammatory effects of statins. Curr Opin Lipidol 22: 165-170.

- Vesterinen HM, Currie GL, Carter S, Mee S, Watzlawick R, et al. (2013) Systematic review and stratified meta-analysis of the efficacy of RhoA and Rho kinase inhibitors in animal models of ischaemic stroke. Syst Rev 2: 33.

- LoGrasso PV, Feng Y (2009) Rho kinase (ROCK) inhibitors and their application to inflammatory disorders. Curr Top Med Chem 9: 704-723.

- Feng Y, LoGrasso PV, Defert O, Li R (2016) Rho Kinase (ROCK) Inhibitors and their therapeutic potential. J Med Chem 59: 2269-2300.

- Satoh S, Kobayashi T, Hitomi A, Ikegaki I, Suzuki Y, et al. (1999) Inhibition of neutrophil migration by a protein kinase inhibitor for the treatment of ischemic brain infarction. Jpn J Pharmacol 80: 41-48.

- Li Y, Wu Y, Wang Z, Zhang XH, Wu WK (2010) Fasudil attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice through the Rho/Rho kinase pathway. Med Sci Monit 16: Br112-118.

- Ding RY, Zhao DM, Zhang ZD, Guo RX, Ma XC (2011) Pretreatment of Rho kinase inhibitor inhibits systemic inflammation and prevents endotoxin-induced acute lung injury in mice. J Surg Res 171: e209-214.

- Liu C, Li Y, Yu J, Feng L, Hou S, et al. (2013) Targeting the shift from M1 to M2 macrophages in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice treated with fasudil. PloS One 8: e54841.

- Liu CY, Guo SD, Yu JZ, Li YH, Zhang H, et al. (2015) Fasudil mediates cell therapy of EAE by immunomodulating encephalomyelitic T cells and macrophages. Eur J Immunol 45: 142-152.

- Gronberg NV, Johansen FF, Kristiansen U, Hasseldam H (2013) Leukocyte infiltration in experimental stroke. J Neuroinflammation 10: 115.

- Rayasam A, Hsu M, Hernandez G, Kijak J, Lindstedt A, et al. (2017) Contrasting roles of immune cells in tissue injury and repair in stroke: the dark and bright side of immunity in the brain. Neurochem Int 107: 104-116.

- Pool M, Rambaldi I, Darlington PJ, Wright MC, Fournier AE, et al. (2012) Neurite outgrowth is differentially impacted by distinct immune cell subsets. Mol Cell Neurosci 49: 68-76.

- Brea D, Agulla J, Rodriguez-Yanez M, Barral D, Ramos-Cabrer P, et al. (2014) Regulatory T cells modulate inflammation and reduce infarct volume in experimental brain ischaemia. J Cell Mol Med 18: 1571-1579.

- Yilmaz G, Arumugam TV, Stokes KY, Granger DN (2006) Role of T lymphocytes and interferon-gamma in ischemic stroke. Circulation 113: 2105-2112.

- Orban PC, Chui D, Marth JD (1992) Tissue- and site-specific DNA recombination in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 6861-6865.

- Pedersen E, Basse A, Lefever T, Peyrollier K, Brakebusch C (2012) Rho GTPase knockout induction in primary keratinocytes from adult mice. Methods Mol Biol 827: 157-166.

- Jacobsen KR, Fauerby N, Raida Z, Kalliokoski O, Hau J, et al. (2013) Effects of buprenorphine and meloxicam analgesia on induced cerebral ischemia in C57BL/6 male mice. Comp Med 63: 105-113.

- Bankhead P, Loughrey MB, Fernández JA, Dombrowski Y, McArt DG, et al. (2017) QuPath: open source software for digital pathology image analysis. bioRxiv.

- Rikitake Y, Liao JK (2005a) Rho GTPases, statins, and nitric oxide. Circ Res 97: 1232-1235.

- Rikitake Y, Kim HH, Huang Z, Seto M, Yano K, et al. (2005b) Inhibition of Rho kinase (ROCK) leads to increased cerebral blood flow and stroke protection. Stroke 36: 2251-2257.

- Vielkind S, Gallagher-Gambarelli M, Gomez M, Hinton HJ, Cantrell DA (2005) Integrin Regulation by RhoA in Thymocytes. J Immunol 175: 350-357.

- Sahai E, Marshall CJ (2003) Differing modes of tumour cell invasion have distinct requirements for Rho/ROCK signalling and extracellular proteolysis. Nat Cell Biol 5: 711-719.

- Devreotes P, Horwitz AR (2015) Signaling networks that regulate cell migration. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7: a005959.

- Ulivieri C, Fanigliulo D, Benati D, Pasini FL, Baldari CT (2008) Simvastatin impairs humoral and cell-mediated immunity in mice by inhibiting lymphocyte homing, T-cell activation and antigen cross-presentation. Eur J Immunol 38: 2832-2844.

- Hou SW, Liu CY, Li YH, Yu JZ, Feng L, et al. (2012) Fasudil ameliorates disease progression in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, acting possibly through antiinflammatory effect. CNS Neurosci Ther 18: 909-917.

- Hara M, Takayasu M, Watanabe K, Noda A, Takagi T, et al. (2000) Protein kinase inhibition by fasudil hydrochloride promotes neurological recovery after spinal cord injury in rats. J Neurosurg 93: 94-101.

- Dangas G, Smith DA, Unger AH, Shao JH, Meraj P, et al. (2000) Pravastatin: an antithrombotic effect independent of the cholesterol-lowering effect. Thromb Haemost 83: 688-692.

- Honjo M, Tanihara H, Nishijima K, Kiryu J, Honda Y, et al. (2002) Statin inhibits leukocyte-endothelial interaction and prevents neuronal death induced by ischemia-reperfusion injury in the rat retina. Arch Ophthalmol 120: 1707-1713.

- Thumkeo D, Shimizu Y, Sakamoto S, Yamada S, Narumiya S (2005) ROCK-I and ROCK-II cooperatively regulate closure of eyelid and ventral body wall in mouse embryo. Genes Cells 10: 825-834.

- Shi J, Wu X, Surma M, Vemula S, Zhang L, et al. (2013) Distinct roles for ROCK1 and ROCK2 in the regulation of cell detachment. Cell Death Dis 4: e483.

- Shi J, Zhang YW, Yang Y, Zhang L, Wei L (2010) ROCK1 plays an essential role in the transition from cardiac hypertrophy to failure in mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol 49: 819-828.

- Yoneda A, Multhaupt HA, Couchman JR (2005) The Rho kinases I and II regulate different aspects of myosin II activity. J Cell Biol 170: 443-453.

- Nakagawa O, Fujisawa K, Ishizaki T, Saito Y, Nakao K, et al. (1996) ROCK-I and ROCK II, two isoforms of Rho-associated coiled-coil forming protein serine/threonine kinase in mice. FEBS Lett 392: 189-193.

- Araki S, Ito M, Kureishi Y, Feng J, Machida H, et al. (2001) Arachidonic acid-induced Ca2+ sensitization of smooth muscle contraction through activation of Rho-kinase. Pflugers Arch 441: 596-603.

- Feng J, Ito M, Kureishi Y, Ichikawa K, Amano M, et al. (1999) Rho-associated kinase of chicken gizzard smooth muscle. J Biol Chem 274: 3744-3752.

- Tang AT, Campbell WB, Nithipatikom K (2012) ROCK1 feedback regulation of the upstream small GTPase RhoA. Cell Signal 24: 1375-1380.

- Abadier M, Haghayegh Jahromi N, Cardoso Alves L, Boscacci R, Vestweber D (2015) Cell surface levels of endothelial ICAM-1 influence the transcellular or paracellular T-cell diapedesis across the blood-brain barrier. Eur J Immunol 45: 1043-1058.

- Etienne-Manneville S, Hall A (2002) Rho GTPases in cell biology. Nature 420: 629-635.

- Jaffe AB, Hall A (2005) Rho GTPases: biochemistry and biology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 21: 247-269.

- Laufs U, Gertz K, Huang P, Nickenig G, Bohm M (2000) Atorvastatin upregulates type III nitric oxide synthase in thrombocytes, decreases platelet activation, and protects from cerebral ischemia in normocholesterolemic mice. Stroke 31: 2442-2449.

- Chen J, Zhang C, Jiang H, Li Y, Zhang L, et al. (2005) Atorvastatin induction of VEGF and BDNF promotes brain plasticity after stroke in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 25: 281-290.

- Koumura A, Hamanaka J, Kawasaki K, Tsuruma K, Shimazawa M, et al. (2011) Fasudil and ozagrel in combination show neuroprotective effects on cerebral infarction after murine middle cerebral artery occlusion. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 338: 337-344.

- Chong CM, Ai N, Lee SM (2017) ROCK in CNS: different roles of isoforms and therapeutic target for neurodegenerative disorders. Curr Drug Targets 18: 455-462.

- Hodge RG, Ridley AJ (2016) Regulating Rho GTPases and their regulators. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 17: 496-510.

- Iadecola C, Anrather J (2011) The immunology of stroke: from mechanisms to translation. Nat Med 17: 796-808.

- Brait VH, Arumugam TV, Drummond GR, Sobey CG (2012) Importance of T lymphocytes in brain injury, immunodeficiency, and recovery after cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 32: 598-611.

- Fu PC, Tang RH, Wan Y, Xie MJ, Wang W, et al. (2016) ROCK inhibition with fasudil promotes early functional recovery of spinal cord injury in rats by enhancing microglia phagocytosis. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci 36: 31-36.

- Fukuta T, Asai T, Sato A, Namba M, Yanagida Y, et al. (2016) Neuroprotection against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by intravenous administration of liposomal fasudil. Int J Pharm 506: 129-137.

- Chen M, Liu A, Ouyang Y, Huang Y, Chao X, et al. (2013) Fasudil and its analogs: a new powerful weapon in the long war against central nervous system disorders? Expert Opin Investig Drugs 22: 537-550.

- Zhou Q, Gensch C, Liao JK (2011) Rho-associated coiled-coil-forming kinases (ROCKs): potential targets for the treatment of atherosclerosis and vascular disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci 32: 167-173.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences